At Pan Toll -- where you can usually find a ranger on duty, at least on weekends, as well as a campground and small but relatively clean restrooms -- walk on the paved road past the restrooms and almost immediately turn to the right down the signed trail to Steep Ravine and Stinson Beach.

At Pan Toll -- where you can usually find a ranger on duty, at least on weekends, as well as a campground and small but relatively clean restrooms -- walk on the paved road past the restrooms and almost immediately turn to the right down the signed trail to Steep Ravine and Stinson Beach.

|

Ĉe Pan Toll -- kie oni kutime povas trovi deĵorantan patroliston, almenaŭ semajnfine, ankaŭ bivakejon kaj malgrandan sed relative puran necesejon -- marŝu laŭ la pavimita vojo preter la necesejon, kaj preskaŭ tuj poste turnu vin dekstren laŭ la indikita pado al Kruta Kanjono kaj Stinson Beach.

|

|

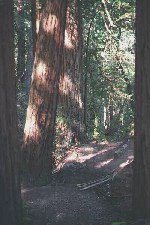

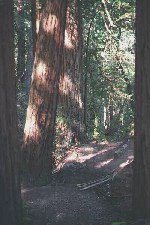

The first part of the trail slants downwards across a north-facing grassy hillside dotted with middle-aged Douglas firs, their trunks looking more aged than they really are because of the lichen growing on them. As you descend a bit below the rim of the canyon, the trees grow closer together, and are joined by California laurel. The canyon grows generally darker, even on sunny days, though I suppose that sun can get in during the late afternoon as it drops to the west. It would be unfair to call Steep Ravine cheerless, however; like any force of nature, it is well beyond cheerlessness, even on its darkest days.

|

La unua parto de la vojo kliniĝas malsupren laŭ nordenfronta herba deklivo punktita de mezaĝaj pseŭtocugoj, kies trunkoj ŝajnas pli grandaĝaj ol ili efektiva estas pro la liĥenoj, kiuj kreskas sur ili. Kiam vi iomete malsupreniras sub la rando de la kanjono, la arboj kreskas pli interproksimaj, kaj kun ili troviĝas kaliforniaj laŭroj. La kanjono ĝenerale malheliĝas, eĉ je sunlumaj tagoj, kvankam mi supozas, ke la suno povas eniri dum la malfrua posttagmezo kiam ĝi falas okcidente. Tamen estus nejuste nomi Krutan Kanjonon trista; kiel ĉia natura forto, ĝi superas tristecon, eĉ je la pli malhelaj tagoj.

La unua parto de la vojo kliniĝas malsupren laŭ nordenfronta herba deklivo punktita de mezaĝaj pseŭtocugoj, kies trunkoj ŝajnas pli grandaĝaj ol ili efektiva estas pro la liĥenoj, kiuj kreskas sur ili. Kiam vi iomete malsupreniras sub la rando de la kanjono, la arboj kreskas pli interproksimaj, kaj kun ili troviĝas kaliforniaj laŭroj. La kanjono ĝenerale malheliĝas, eĉ je sunlumaj tagoj, kvankam mi supozas, ke la suno povas eniri dum la malfrua posttagmezo kiam ĝi falas okcidente. Tamen estus nejuste nomi Krutan Kanjonon trista; kiel ĉia natura forto, ĝi superas tristecon, eĉ je la pli malhelaj tagoj.

|

|

In the springtime, there are a large number of wild flowers growing along the sides of the canyon, but this year it looks as though the canyon will be following the Western Christian calendar rather than the neo-pagan or Chinese calendars; I saw not a flower until I had dropped at least five hundred feet from Pan Toll. Nevertheless, there were plenty of ferns, mostly the common sword fern, growing along both sides of the canyon, as well as enough moss on the trees and ground to make you think that this is the most common plant in the world, which it may well be.

|

Printempe kreskas multaj sovaĝaj floroj laŭ la flankoj de la kanjono, sed en 1996 ŝajnas, ke la kanjono obeos la Okcidentkristanan kalendaron kaj ne la novpaganajn aŭ ĉinajn kalendarojn; mi vidis eĉ ne unu floron ĝis mi malsupreniris almenaŭ 150 metrojn de Pan Toll. Tamen, troviĝis multaj filikoj, ĉefe la ordinaraj glavofilikoj, kiuj kreskis laŭ ambaŭ flankoj de la kanjono, kaj ankaŭ sufiĉe da musko sur la arboj kaj tero por supozigi, ke temas pri la plej ofte vegetaĵo en la mondo, kio eble estas ĝusta.

|

The trail switchbacks down through the Douglas firs and laurels and eventually reaches the bottom of the canyon, where Webb Creek rages along westward on its short but enthusiastic course to the sea (in summer it will turn into a mere trickle, and this high up may even be dry). Here in the bottom the trees change form and become redwoods, with some really beautiful groves this high up -- further down they will spread out a bit and become more isolated from each other. Watch for two crossings of Webb Creek, only a few hundred feet apart, neither one of them with a bridge (you may get your feet wet); between them is a little spring, off to the right side of the trail, which in any season drains down onto the trail and turns it to mud, even when the rest of the trail is dust dry.

The trail switchbacks down through the Douglas firs and laurels and eventually reaches the bottom of the canyon, where Webb Creek rages along westward on its short but enthusiastic course to the sea (in summer it will turn into a mere trickle, and this high up may even be dry). Here in the bottom the trees change form and become redwoods, with some really beautiful groves this high up -- further down they will spread out a bit and become more isolated from each other. Watch for two crossings of Webb Creek, only a few hundred feet apart, neither one of them with a bridge (you may get your feet wet); between them is a little spring, off to the right side of the trail, which in any season drains down onto the trail and turns it to mud, even when the rest of the trail is dust dry.

|

La vojo zigzagas malsupren tra la pseŭdocugoj kaj laŭroj kaj finfine atingis la fundon de la kanjono, kie Rivereto Webb furiozas okcidenten laŭ sia mallonga sed entuziasma vojo al la maro (somere ĝi fariĝos nura flueto, kaj ĉe ĉi tiu alteco eble eĉ sekos). Ĉi tie en la fundo, la arboj ŝanĝas siajn formojn kaj fariĝas sekvojoj, kun kelkaj vere belaj arbaretoj je ĉi tiu nivelo -- pli malsupere, ili iomete apartiĝos, kaj fariĝos pli izolitaj. Rimarku la du transirojn de Rivereto Webb, apartaj eble nur cent metrojn; mankas al ili pontojn (vi eble malsekigos al vi la piedojn); inter ili estas fonteto, iomete dekstre de la pado, kiu ĉiusezono dreniĝas al la vojo kaj kotigas ĝin, eĉ kiam la cetero restas polve seka.

|

|

Once you have crossed the stream for the second time you will remain on or above its south bank for quite some time, through dark, thick redwood forest, dense with ferns and other plants. Keep an eye out for two or three trees whose heartwood has been burned out -- good places to take refuge from rain showers -- and for a twin pair of trees between which you have to step; this marks the end of the grove area, and below here the ravine becomes a bit lighter.

|

Duan fojon transirinte la rivereton, vi dum iom da tempo restas sur aŭ super ĝia suda bordo, tra malhela arbaro, densa je sekvojoj, filikoj kaj aliaj plantaĵoj. Serĉu du-tri arbojn, kies korligno estas forbruligita -- bonaj lokoj por rifuĝi de ekpluvoj -- kaj ĝemelan arboduopon, inter kiuj vi devos paŝi; jen la fino de la arbareta regiono, kaj malsupre la kanjono fariĝas iom pli hela.

Duan fojon transirinte la rivereton, vi dum iom da tempo restas sur aŭ super ĝia suda bordo, tra malhela arbaro, densa je sekvojoj, filikoj kaj aliaj plantaĵoj. Serĉu du-tri arbojn, kies korligno estas forbruligita -- bonaj lokoj por rifuĝi de ekpluvoj -- kaj ĝemelan arboduopon, inter kiuj vi devos paŝi; jen la fino de la arbareta regiono, kaj malsupre la kanjono fariĝas iom pli hela.

|

One of the major problems along the Steep Ravine trail is fallen trees; after a stormy winter there will always be a few lying across the trail. One year the trail was actually closed for a month or so because of them (a ranger explained to me that they didn't want to clear them because there were "owls nesting in them"). This year I counted four or five along the route; two of them had fallen within a few feet of locations where the trail had been blocked in previous years by similarly fallen trees. The trunk of one was large enough that someone had felt the need to provide help in getting across; a large bolt was driven into the upward side, to hold onto while you scrambled from one side to another.

One of the major problems along the Steep Ravine trail is fallen trees; after a stormy winter there will always be a few lying across the trail. One year the trail was actually closed for a month or so because of them (a ranger explained to me that they didn't want to clear them because there were "owls nesting in them"). This year I counted four or five along the route; two of them had fallen within a few feet of locations where the trail had been blocked in previous years by similarly fallen trees. The trunk of one was large enough that someone had felt the need to provide help in getting across; a large bolt was driven into the upward side, to hold onto while you scrambled from one side to another.

|

Unu el la ĉefaj problemoj laŭ la vojo de Kruta Kanjono estas la falintaj arboj; post tempesta vintro, ĉiam estos kelkaj laŭ la vojo. Unu jaron oni efektive fermis la vojon pro ili dum unu-du monatoj (patrolisto klarigis al mi, ke ili ne volas forigi ilin, ĉar "strigoj nestas en ili"). Ĉijare mi kalkulis kvar-kvin laŭ la vojo; du falis nur kelkajn metrojn for de lokoj, kie en antaŭaj jaroj la vojo obstrukciiĝis pro simile falintaj arboj. La trunko de unu estis sufiĉe granda, ke iu sentis la bezonon provizi helpon por transiri; granda sekurigilo estas martelita en unu flanko, por teni dum oni rampas de unu flanko al alia.

|

|

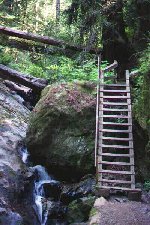

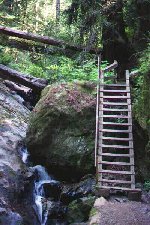

A major feature of the Steep Ravine trail is the Ladder. About halfway from Pan Toll to the Dipsea junction you descend through a narrow cleft on rock steps and come out at the top of the ladder, which is made of wood and has about fifteen steps; it lies alongside a major cataract in Webb Creek. Be careful descending it; when wet (often!) the wood can be slippery, and I am not too sure about how strong all the rungs are -- in 1995 one of them broke, though it has since been replaced. It's probably best to let those coming up wait until you get down rather than trying to make way for them; there's plenty of room for a lot of people to stand below the ladder, but at the top the only open space is on a boulder overlooking the plunge of the waterfall -- not the safest of stances, though an invigorating one, and certainly not roomy enough for more than one person at a time.

|

Ĉefa ejo laŭ la vojo de Kruta Kanjono estas la Ŝtupetaro. Proks. duonvoje inter Pan Toll kaj la Vojkruciĝo Dipsea, vi malsupreniras tra mallarĝa fendo sur rokaj ŝtupoj kaj atingas la supron de la ŝtupetaro, kiu estas farita el ligno kaj havas proksimume 15 ŝtupetojn; ĝi kuŝas apud ĉefa falakvo de Rivereto Webb. Gardu vin, malsuprenirante laŭ ĝi; kiam ĝi malsekas (ofte!), la ligno povas esti glitiga, kaj mi ne certas pri la fortikeco de la ŝtupetoj -- en 1995, unu el ili rompiĝas, tamen oni poste refaris ĝin. Estas pli bone atendigi tiujn, kiuj suprenvenos, ol mem lasi vojon por ili; estas multe da spaco por staradu sub la ŝtupetaro, sed supre la sola spaco estas sur rukego super la falakva plonĝo -- starloko eble vigliga, tamen ne tre sekura, kaj certe ne sufiĉe spaca por pli ol unu persono.

Ĉefa ejo laŭ la vojo de Kruta Kanjono estas la Ŝtupetaro. Proks. duonvoje inter Pan Toll kaj la Vojkruciĝo Dipsea, vi malsupreniras tra mallarĝa fendo sur rokaj ŝtupoj kaj atingas la supron de la ŝtupetaro, kiu estas farita el ligno kaj havas proksimume 15 ŝtupetojn; ĝi kuŝas apud ĉefa falakvo de Rivereto Webb. Gardu vin, malsuprenirante laŭ ĝi; kiam ĝi malsekas (ofte!), la ligno povas esti glitiga, kaj mi ne certas pri la fortikeco de la ŝtupetoj -- en 1995, unu el ili rompiĝas, tamen oni poste refaris ĝin. Estas pli bone atendigi tiujn, kiuj suprenvenos, ol mem lasi vojon por ili; estas multe da spaco por staradu sub la ŝtupetaro, sed supre la sola spaco estas sur rukego super la falakva plonĝo -- starloko eble vigliga, tamen ne tre sekura, kaj certe ne sufiĉe spaca por pli ol unu persono.

|

Below the ladder I started seeing flowers. The most noticeable ones were trilliums. Most of the trilliums had not yet opened their buds, but a few disspirited looking flowers were already out; I suppose that by the second half of March the whole canyon will be in bloom. There were a few other flowers, but for a whole gamut of types I had to wait for the Dipsea Trail (see below).

Below the ladder I started seeing flowers. The most noticeable ones were trilliums. Most of the trilliums had not yet opened their buds, but a few disspirited looking flowers were already out; I suppose that by the second half of March the whole canyon will be in bloom. There were a few other flowers, but for a whole gamut of types I had to wait for the Dipsea Trail (see below).

|

Sub la ŝtupetaro, mi komencis vidi florojn. Plej rimarkindaj estis la trilioj. La plimultaj trilioj ankoraŭ ne malfermis la burĝonetojn, sed kelkaj malfeliĉaspektaj floroj jam aperis; mi supozas, ke antaŭ la dua parto de marto la tuta kanjono estos ekflorinta. Estis pluraj aliaj floroj, sed por tuta gamo da specoj, mi devis atendi la Vojon Dipsea (vidu malsupere).

|

|

You follow along the canyon as it widens and then narrows again, and a quarter mile or so beyond the ladder you descend to a wooden bridge that crosses to the north side of the creek. Here, after crossing, you will see to your left a wide rocky area where the creek drops into some little pools, then plummets over the edge into a major pool far below. I don't know if this area has a particular name, but I call it "Rocks of Repose" because I usually take a break here to enjoy the stream and what would be the shade of several huge overhanging trees, if there were ever any sun to shade you from... Take a rest here and enjoy the locale for yourself.

|

Sekvu laŭ la kanjono dum ĝi plilarĝiĝas kaj poste remallarĝiĝas, kaj duonkilometron preter la ŝtupetaro vi malsupreniras al ligna ponto, kiu transiras al la norda flanko de la rivereto. Ĉi tie, transirinte, vi vidos maldekstre larĝan rokan spacon, kie la rivereto falas al kelkaj lagetoj, poste plonĝas trans la rando al granda lageto longe malsupere. Mi ne scias, ĉu tiu loko havas specialan nomon, sed mi mem nomas ĝin "Rokoj de Ripozo" ĉar mi kutime ekripozas tie por ĝui la rivereton kaj la ŝirmo de kelkaj grandaj superpendantaj arboj, se estus suno kontraŭ kiu ŝirmi vin... Ĉi tie ripozu kaj mem ĝuu la lokon.

Sekvu laŭ la kanjono dum ĝi plilarĝiĝas kaj poste remallarĝiĝas, kaj duonkilometron preter la ŝtupetaro vi malsupreniras al ligna ponto, kiu transiras al la norda flanko de la rivereto. Ĉi tie, transirinte, vi vidos maldekstre larĝan rokan spacon, kie la rivereto falas al kelkaj lagetoj, poste plonĝas trans la rando al granda lageto longe malsupere. Mi ne scias, ĉu tiu loko havas specialan nomon, sed mi mem nomas ĝin "Rokoj de Ripozo" ĉar mi kutime ekripozas tie por ĝui la rivereton kaj la ŝirmo de kelkaj grandaj superpendantaj arboj, se estus suno kontraŭ kiu ŝirmi vin... Ĉi tie ripozu kaj mem ĝuu la lokon.

|

|

You now descend some distance on rocky steps, following the plunging creek, and continue on through relatively open forest. When you come to a point where the trail passes between a vertical rock wall on the right and a nice redwood log that appears to have been turned into a huge bench on your left, you will be almost to the Dipsea junction, which comes in sight ahead of you in another minute, with another wooden bridge crossing the stream to your left, and a vertical signpost indicating the various routes you can take.

|

Nun iom malsupreniru laŭ rokaj ŝtupoj, laŭ la plonĝanta rivereto, kaj daŭrigu tra relative maldensa arbaro. Kiam vi atingos lokon, kie la vojeto trairas inter vertikala roka muro dekstre kaj bela sekvoja trunko, ŝajne skulptita al grandega benko, maldekstre, jen vi estos preskaŭ atinginta la Vojkruciĝo Dipsea, kiu ekvidebliĝas antaŭ vi post ankoraŭ minuto, kun alia ligna ponto transiranta la ponton maldekstre, kaj vertikala signofosto, kiu indikas la diversajn vojojn, kiujn vi povas sekvi.

|

The Dipsea and Steep Ravine trails now run together for some distance -- some very little distance, that is; not more than a hundred yards. Below the bridge, the stream widens into a pool in the summer, a pool from which water is sucked out to be lifted to a wooden tank far up in the woods to your right (you can see it from the Panoramic Highway). In the winter, the dam that creates the pool is opened and water is allowed to run free. I originally thought that the dam had broken in one particularly stormy winter, but after the spillway was seen to be open in quite a number of winters I came to the conclusion that the gate's disappearance was quite deliberate.

The Dipsea and Steep Ravine trails now run together for some distance -- some very little distance, that is; not more than a hundred yards. Below the bridge, the stream widens into a pool in the summer, a pool from which water is sucked out to be lifted to a wooden tank far up in the woods to your right (you can see it from the Panoramic Highway). In the winter, the dam that creates the pool is opened and water is allowed to run free. I originally thought that the dam had broken in one particularly stormy winter, but after the spillway was seen to be open in quite a number of winters I came to the conclusion that the gate's disappearance was quite deliberate.

|

La vojoj Dipsea kaj Kruta Kanjono nun iom kunkondukas -- tamen nelonge; ne pli ol cent metrojn. Sub la ponto, la rivereto somere fariĝas lageto, el kiu oni suĉas akvon kaj levas ĝin al ligna cisterno supere en la dekstra arbaro (vi povas tion vidi de la Panorama Ŝoseo). Vintre, oni malfermas la baraĵon kiu kreis la lageton, kaj permesas, ke la akvo libere flui. Mi komenci kredis, ke la baraĵo rompiĝis en unu aparte tempesta vintro, sed post kiam la defluilo montriĝas malfermita dum pluraj vintroj, mi konkludis, ke la malapero de la barilo estis tute intenca.

|

|

There's a maze of trails through the woods immediately below the dam; your best bet is to turn up the one that has a small pipe running up the middle, going off to your right. In about a hundred more feet the Steep Ravine trail splits off again, running down into the woods to the left, to follow the ravine the rest of the way out to highway 1 about a mile south of Stinson Beach. We usually follow the Dipsea trail into Stinson Beach, keeping straight ahead here.

|

Miksaĵo da vojetoj trairas la arbaron sub la baraĵo; pli bone, vi turnu vin laŭ tiu kun mallarĝa pipo en la mezo; ĝi kondukas dekstren. Post eble 30 metroj la vojo de Kruta Kanjono denove disiĝas, kondukante malsupren tra la arbaro maldekstre, sekvanta la kanjonon la ceteran distancon al ŝoseo 1 eble du kilometrojn sude de Stinson Beach. Ni mem kutime sekvas la vojon Dipsea al Stinson Beach, kaj daŭrigas rekte antaŭen.

|

|

This little stretch is the only major uphill pull along the route, and it is the one that brings you out of eternal shade into sunshine -- or fog, as the case may be. After a moderate climb of a hundred yards or so, you come to a small fire road. Cross it, and continue to climb to a ridge from which the entire panorama of the Stinson Beach-Bolinas coastline, including the Stinson Beach sand spit, Bolinas Lagoon, and the southern end of Point Reyes can be seen -- one of the most beautiful views in northern California. And if the day is foggy, you can at least imagine it.

|

Tiu mallonga vojparto estas la sola signifohava supreniro laŭ la vojo, kaj ĝi elkondukos vin el la eterna ombro al sunlumo -- aŭ nebulo, depende de la vetero, Post modera supreniro centmetra, vi atingos malgrandan fajrobrigadan vojon. Transiru ĝin, daŭrigu la supreniron al firsto, de kiu videblas la tuta panoramo de la marbordo Stinson Beach-Bolinas, kun la sabloetendaĵo de Stinson Beach, Laguno Bolinas, kaj la suda parto de Point Reyes -- unu el la plej belaj vidindaĵoj en norda Kalifornio. Kaj se la tago estas nebula, vi povas almenaŭ enmense bildigi ĝin al vi...

Tiu mallonga vojparto estas la sola signifohava supreniro laŭ la vojo, kaj ĝi elkondukos vin el la eterna ombro al sunlumo -- aŭ nebulo, depende de la vetero, Post modera supreniro centmetra, vi atingos malgrandan fajrobrigadan vojon. Transiru ĝin, daŭrigu la supreniron al firsto, de kiu videblas la tuta panoramo de la marbordo Stinson Beach-Bolinas, kun la sabloetendaĵo de Stinson Beach, Laguno Bolinas, kaj la suda parto de Point Reyes -- unu el la plej belaj vidindaĵoj en norda Kalifornio. Kaj se la tago estas nebula, vi povas almenaŭ enmense bildigi ĝin al vi...

|

From here you drop down to another fire road. Watch for fields of thistle in bloom late in the season; for those who know this plant only as a prickly annoyance, a first look at its beautiful round purple flowers (here they will be asccompanied by bumblebees en masse) will make you understand why the Scots chose this as their national emblem. If you want a side jaunt, turn left here and follow the road southwest until you come to the large tree you see off in that direction; then cast about downhill from the tree towards the highway, and you will find five old military spy holes, used to triangulate cannon fire from the batteries to the south in case of enemy invasion -- now abandoned to their fate, victims of a technological age with radar PPI and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

From here you drop down to another fire road. Watch for fields of thistle in bloom late in the season; for those who know this plant only as a prickly annoyance, a first look at its beautiful round purple flowers (here they will be asccompanied by bumblebees en masse) will make you understand why the Scots chose this as their national emblem. If you want a side jaunt, turn left here and follow the road southwest until you come to the large tree you see off in that direction; then cast about downhill from the tree towards the highway, and you will find five old military spy holes, used to triangulate cannon fire from the batteries to the south in case of enemy invasion -- now abandoned to their fate, victims of a technological age with radar PPI and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

|

De ĉi tie vi malsupreniras al ankoraŭ unu fajrobrigada vojo. Rigardu la kampoj da kardoj malfrusezone florantaj; por tiuj konantaj tiuj plantaĵon nur kiel pikeman ĝenaĵon, unua vido de la belaj rondaj purpuraj floroj (ĉi tie ilin amase akompanos burdoj) komprenigos vin, kial la skotoj elektis tiun floron kiel sian nacian floron. Se vi deziras flankan ekskurson, ĉi tie turnu vin maldekstren kaj sekvu la vojon sudokcidenten ĝis vi atingos la arbegon, kiun vi vidas tiudirekte; poste, serĉu sur la malsuprenira dekliva inter arbo kaj ŝoseo, kaj vi trovos kvin malnovajn militistajn gvatejojn, kiun oni uzis por trianguligi kanonpafadon de la sudaj baterioj okaze de malamika invado -- nun ili estas forlasitaj al sia sorto, viktimoj de teĥna epoko kun radara PPI kaj interkontinentaj misiloj.

De ĉi tie vi malsupreniras al ankoraŭ unu fajrobrigada vojo. Rigardu la kampoj da kardoj malfrusezone florantaj; por tiuj konantaj tiuj plantaĵon nur kiel pikeman ĝenaĵon, unua vido de la belaj rondaj purpuraj floroj (ĉi tie ilin amase akompanos burdoj) komprenigos vin, kial la skotoj elektis tiun floron kiel sian nacian floron. Se vi deziras flankan ekskurson, ĉi tie turnu vin maldekstren kaj sekvu la vojon sudokcidenten ĝis vi atingos la arbegon, kiun vi vidas tiudirekte; poste, serĉu sur la malsuprenira dekliva inter arbo kaj ŝoseo, kaj vi trovos kvin malnovajn militistajn gvatejojn, kiun oni uzis por trianguligi kanonpafadon de la sudaj baterioj okaze de malamika invado -- nun ili estas forlasitaj al sia sorto, viktimoj de teĥna epoko kun radara PPI kaj interkontinentaj misiloj.

|

|

If you went to the spy holes, you can follow back north along the ridge, traveling rough until you reach the Dipsea trail again, somewhere below where you left it (watch for tiny trees and strange plants growing in the "UFO landing site" that you will cross, and, in summer or fall, expect to spend much time picking foxtails out of your pants and socks after you get to the end of your walk). Otherwise, just continue on down the trail, through a low valley from which the ocean is no longer visible and then up over another low open ridge. From here you will descend north, with bushes growing ever taller around you. A brush-covered rockpile to your left may attract you to enjoy its views; however, it is not particularly easy to bushwhack your way to the top. Along here you can see quite a number of flowers, even in early season, including but not limited to sticky monkey flower, Douglas iris, and the ubiquitous bramble, which by late summer will be quite ready to feed you with delicious blackberries, if the birds don't beat you to it.

|

Se vi vizitis la gvatejojn, vi povas reiri norden laŭ la firsto, senvoje irante ĝis vi reatingos la vojon Dipsea, ie sub la loko, kie vi lasis ĝin (rimarku la arbetojn kaj strangajn plantaĵoj, kiuj kreskas en la "NIFO-surteriĝejo" kiun vi devos transiri, kaj, somere kaj aŭtune, vi devos poste pasigi multe da tempo plukante piksemojn el viaj pantalono kaj ŝtrumpoj, atinginte la finon de la ekskurso). Aliel, nur daŭrigu laŭ la vojon, tra malalta valo de kiu la maro ne plu videblas, poste supren trans ankoraŭ unu malalta senarba firsto. De tie, vi malsupreniros norden, kun arbustoj kiuj ĉiam pli alte kreskas ĉirkaŭ vi. Arbustokovrita rokamaso maldekstre de vi eble allogos vin por ĝui vidojn de ĝia supro; tamen, ne estas aparte facile traŝovi vin al la supro. Laŭ ĉi tiu vojparto vi povas vidi multajn florojn, eĉ frusezone; temas (sed ne nur) pri la glueca simifloro, Douglas-iriso, kaj la ĉie-trovebla rubuso, kiu malfrusomere pretos nutri vin per bongustegaj beroj, se la birdoj ne estos antaŭintaj vin...

|

|

The little forest ahead looks slightly unusual; the tops of its trees are typical of the coastal area, shaped by the wind to make a continuous dome over the landscape; these are, I think, California buckeyes for the most part. I have regaled my children for years with the story that this "enchanted wood" contains elves, gnomes, dwarves and other less savory creatures, and that of ten hikers entering the wood only nine emerge. (I admit that my statistics may be off -- so far we haven't lost anybody.) The wood is far more open on the inside than it looks from the outside. You descend steeply through it and, after passing a number of gnarled-looking grandparent trees, you emerge into a typical marshland, complete with boardwalk to keep you above the mud. Beyond this, you drop down to meet the Panoramic Highway, just above its junction with highway 1.

|

La eta arbaro antaŭ vi aspektas iomete nekutima; la arbosuproj estas tipaj pri la marborda regiono, formitaj de la vento por fari senfendan kupolon super la pejzaĝo; tiuj estas, mi opinias, pliparte kaliforniaj polparboj. Mi dum jaroj regalis miajn gefilojn per la rakonto, ke tiu "sorĉarbaro" enhavas elfojn, gnomojn, kaj aliajn malpli bonajn estaĵojn, kaj ke el dek ekskursantoj enirintaj la arbaron, nur naŭ elvenas. (Mi konfesas, ke mia statistiko eble estas erara -- ĝis nun, ni perdis neniun.) La arbaro estas multe malpli densa interne ol ŝajnas de ekstere. Vi krute malsupreniras tra ĝin kaj, preteririnte kelkajn tordaspektajn avarbojn, vi elvenos al tipa marĉo, kun ponto-trotuaro por protekti vin de la koto. Pretere, vi malsupreniros por atingi la Panoraman Ŝoseon, proksime al ties kuniĝo kun ŝoseo 1.

|

If you have a car waiting for you in the park area, cross the Panoramic Highway and drop down to highway 1; then cross it (after getting some blackberries on the east side of the road -- in season, of course), and go north along the west side until you reach a road that turns left. Go down this road, keeping right at the immediate fork, for about a quarter of a mile; past the restaurant and snack shop you'll find a bridge across a stream and an opening in the park fence, through which lies the picnic area and parking lot. If you have time to kill, a visit to the beach is in order; aside from the beauties of ocean, sun and sand, you'll find plenty to interest you lying around in the sun picking up a tan -- again, in season.

If you have a car waiting for you in the park area, cross the Panoramic Highway and drop down to highway 1; then cross it (after getting some blackberries on the east side of the road -- in season, of course), and go north along the west side until you reach a road that turns left. Go down this road, keeping right at the immediate fork, for about a quarter of a mile; past the restaurant and snack shop you'll find a bridge across a stream and an opening in the park fence, through which lies the picnic area and parking lot. If you have time to kill, a visit to the beach is in order; aside from the beauties of ocean, sun and sand, you'll find plenty to interest you lying around in the sun picking up a tan -- again, in season.

|

Se aŭto atendas vin en la parko, transiru la Panoraman Ŝoseon kaj malsupreniru al ŝoseo 1; transiru ĝin (haviginte al vi kelkajn berojn ĉe la orienta flanko de la vojo -- en ĝusta sezono, kompreneble), kaj iru norden laŭ la okcidenta flanko ĝis vi atingos vojon, kiu iras maldekstren. Laŭiru tiun vojon, restante dekstre ĉe la tuja disbranĉiĝo, dum duonkilometro; preter la restoracio kaj lunĉejo vi trovos ponton trans rivereto, kaj trairejon en la parka barilo, preter kiu kuŝas la piknikejo kaj aŭtolasejo. Se vi disponas tempon, valoras vizito sur la strando; krom la belaĵojn de la maro, la suno kaj la sablo, vi trovos multajn interesaĵojn, kiuj kuŝas en la suno por brunigi sian haŭton -- ankoraŭfoje, en ĝusta sezono.

|

|

Different peoples have set the beginning of spring at different times -- and I am not now talking about the understandable differences between the northern and southern hemispheres. This comes from the varying nature of calendars. The current neo-pagan calendar (far from standardized) is essentially a solar calendar, though lunar phases will be included to make proper scheduling of esbats possible. The Chinese calendar is a lunar-solar calendar; the seasons are placed according to the sun, but their beginnings (at least that of springtime) are a function of phases of the moon. The Western Christian calendar, which is currently the most commonly used, is fundamentally a climatic calendar, but includes solar influences (to determine the starting dates of the seasons) and even some relict lunar influences (the exact date of Easter, for instance).

|

Diversaj popoloj komencis la printempon je diversaj datoj -- kaj mi nun ne parolas pri la kompreneblaj malsamecoj inter la norda kaj suda duonsferoj. Ĉi tiu venas el la varia naturo de kalendaraj. La aktuala novpagana kalendaro (tute ne normigita) estas esenca sunkalendaro, kvankam oni enkludas lunfazojn por ĝuste aranĝi esbatojn. La ĉina kalendaro estas lunsuna kalendaro; oni aranĝas la sezonojn laŭ la suno, sed iliaj komenciĝoj (almenaŭ tiu de la printempo) estas funkcio de la lunfazoj. La Okcidentkristana kalendaro, aktuale la plej ofte uzata, estas fundamenta klimata kalendaro, sed enhavas sunajn influojn (por konstanti la komencdatojn de la sezonoj), kaj eĉ kelkajn restantajn lunajn influojn (ekzemple, la precizan daton de Pasko).

|

|

When does spring begin? For neo-pagans, it begins on or about February 2, which is (more or less) a cross-quarter day known to the Celts as Imbolc (or Imbolg, or Imbeolg, or half a dozen other variant names). This puts the middle of spring, more or less, on or about the vernal equinox (March 21 or 22), and similarly puts the middle of summer, for instance, on or about the summer solstice (June 21) -- which explains why traditionally this date, which marks the beginning of the Western Christian summer, is called "Midsummer". The date of Imbolc was taken over by the Western Church quite early and turned into a once major celebration, "Candlemas". Like most of the other cross-quarter days it has since faded into obscurity (though in parts of rural Oregon kids were celebrating Beltane, Mayday, the beginning of summer at least as late as the early 1950s); the only cross-quarter day that has survived in our society at the end of the 20th century is Halloween (Samhain), and it appears to be on the chopping block as well -- though it is well to remember that such holidays often appear to have lives of their own (Oliver Cromwell's two-decade program to exterminate Christmas as a pagan holiday ultimately failed). Nonetheless, some of these old holidays survive under different guises; Beltane, for example, shows up as Mayday, the global workers' holiday (which the powers-that-be in the United States have done their best to eradicate, providing a substitute "Labor Day" in September). And Imbolc still survives -- even, to some degree, fulfilling its old function as the beginning of springtime -- as "Groundhog Day", when, if the groundhog fails to see his shadow, spring will begin, the official date on the calendar notwithstanding.

|

Kiam komenciĝas la printempo? Por novpaganoj, ĝi komenciĝas je, aŭ proksime al, la 2a de februaro, kiu estas (pli-malpli) mezkvarona tago konata de la keltoj kiel Imbolc (aŭ Imbolg, aŭ Imbeolg, aŭ aliaj variaĵoj). Tio okazigas la printempmezon je, pli-malpli. la printempa ekvinokso (21a aŭ 22a de marto), kaj simile metas la somermezon, ekzemple, je pli-malpli la somera solstico (21a de junio) -- kio klarigas kial, tradicie, tiun daton, markantan la komenciĝon de la Okcidentkristana somero, oni nomas "Somermezo". La daton de Imbolc tre frue transprenis la Okcidenta Eklezio, kiu faris ĝin iam gravan celebron, "Kandelmeso". Same kiel la aliaj mezkvaronaj tagoj, ĝi poste malaperis en obskurecon (kvankam en partoj de kampara Oregonio infanoj ankoraŭ festis Beltenon, Majtagon, la komencon de la somero, almenaŭ en la mezo de la 20a jarcento); la sola mezkvarona tago postvivinta en nia societo fine de la 20a jarcento estas la Saveno, la Festo de Ĉiuj Sanktuloj, kaj ankaŭ ĝi ŝajnas destinita por morto -- kvankam estas memorinde, ke tiaj festotagoj ŝajne havas la proprajn vivojn (la du-jardeka pogromo de Oliver Cromwell kontraŭ la Kristnasko pro ĝia paganeco finfine malsukcesis). Tamen, kelkaj el tiuj malnovaj festotagoj iel pluvivas sub aliaj maskoj; Belteno, ekzemple, reaperis kiel Majtago, la tutmonda festo de la laboristoj (kiun la regantaj potencoj en Usono delonge provas ekstermi, provizante anstataŭan "Labortagon" en septembro). Kaj Imbol ankoraŭ pluvivas -- eĉ, ĝis iu grado, plenumante sian antaŭlongan funkcion kiel la komenciĝon de la printempo -- kiel "Marmota Tago", kiam, se la marmota ne vidas sian ombron, la printempo komenciĝas, malgraŭ la oficiala dato sur la kalendaro.

|

|

Many other cultures have put the beginning of spring considerably earlier than we do. For the Romans, for instance, it occurred at the festival of lupercalia, which, from the description in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, was most definitely a springtime fertility rite; this survives, as others have pointed out, in St. Valentine's Day, slightly before the middle of February (for dramatic purposes, Shakespeare took the liberty of moving the Lupercal back about a month to one or two nights before the Ides of March).

|

Multaj aliaj kulturoj komencis la printempon multe pli frue ol ni. Por la romianoj, ekzemple, tio okazis je la festo de lupercalia, kiu, laŭ la priskribo en Julio Cezaro de Ŝekspiro, estas certe printempa fekundiga rito; tio postvivas, kiel aliaj menciis, en la Tago de Sankta Valenteno, iomete antaŭ la mezo de februaro (por la dramo, Ŝekspiro ŝanĝis la daton iomete ĝis tuj antaŭ la Iduso de Marto).

|

|

For the Chinese, with their lunar-solar calendar, the seasons cover more or less the same periods as they do on the neo-pagan calendar, but their starting dates are moveable, depending on the phases of the moon. Many Americans are familiar with the Chinese New Year (with Easter, one of the only two major American holidays whose date is determined by the moon), but fewer realize that as the beginning of the two-week Spring Festival it marks the beginning of the Chinese spring; it can fall anytime from the end of January to early March, but usually sometime in the first half of February.

|

Por la ĉinoj, kies kalendaro estas lunsuna, la sezonoj kovras pli-malpli la samajn tempodaŭrojn kiel en la novpagana kalendaro, sed iliaj komencdatoj estas moveblaj, laŭ la lunfazoj. Multaj usonanoj konas la Ĉinan Novjaron (kun Pasko, unu el sole du gravaj usonaj festotagoj, kies daton oni konstatas per la luno), sed malpli multaj scias, ke, kiel la komenciĝo de la dusemajna Printempa Festo, ĝi signas la komencon de la ĉina printempo; ĝi povas fali iam ajn inter la fino de januaro kaj la frua marto, sed kutime iam frue en februaro.

|

|

The Western Christian calendar, with which we are all familiar, adjusts the seasons to fit the most common temperate-zone climates rather than the movement of the sun; weather patterns, after all, usually lag the sun by a month or so, which is why northern California's rainy season generally extends from mid-November to the end of March rather than from sometime in October until the end of February, symmetrically around the winter solstice. Given that the seasons were shifted forwards by so much in this calendar, I suppose that it simply seemed convenient to place their beginnings on the old mid-season dates, the easily determinable solstices and equinoxes. Which is why we generally consider spring to begin on March 21 rather than on February 2, February 14 (Roman), or in late February (Chinese, 1996).

|

La Okcidentkristana kalendaro, kiun ni ĉiuj konas, ĝustigas la sezonojn por kongrui kun la plej oftaj mezaj klimatoj, ne la movado de la suno; klimataj normoj, cetere, kutime sekvas la sunon je unu-du monatoj, pro kio la nordkalifornia pluvsezono ĝenerale daŭras de la novembra mezo ĝis la marta fino kaj ne de oktobro ĝis la fino de februaro, simetrie ĉirkaŭ la vintra solstico. Pro tio, ke oni malantaŭenmovis la sezonojn tiom en tiu kalendaro, mi supozas, ke simple oportunis meti la komencdatojn je la antaŭlongaj sezonmezaj datoj, la facile konstateblaj ekvinoksoj kaj solsticoj. Tial ni ĝenerale metas la komencon de printempo je la 21a de marto, ne je la 2a de februaro, la 14a de februaro, aŭ malfrue en februaro (ĉina, 1996).

|

|

Flowers, of course, like to pay more attention to the sun than to the weather patterns, which is why, even in late winter, if the weather turns unseasonally warm and sunny for any length of time trees and plants will explode into bloom -- with unfortunate results if a new cold snap hits. Generally they will follow a solar rather than climatic cycle.

|

La floroj, kompreneble, preferas pli atenti la sunon ol la klimaton, pro kio, eĉ en malfrua vintro, se la vetero fariĝas "ekstersezone" varmeta kaj suna dum iom da tempo, arboj kaj plantaĵoj ekfloros -- kun bedaŭrindaj rezultoj, se remalvarmiĝos. Ĝenerale ili sekvas sunan, ne klimatan, ciklon.

|

At Pan Toll -- where you can usually find a ranger on duty, at least on weekends, as well as a campground and small but relatively clean restrooms -- walk on the paved road past the restrooms and almost immediately turn to the right down the signed trail to Steep Ravine and Stinson Beach.

At Pan Toll -- where you can usually find a ranger on duty, at least on weekends, as well as a campground and small but relatively clean restrooms -- walk on the paved road past the restrooms and almost immediately turn to the right down the signed trail to Steep Ravine and Stinson Beach.

La unua parto de la vojo kliniĝas malsupren laŭ nordenfronta herba deklivo punktita de mezaĝaj pseŭtocugoj, kies trunkoj ŝajnas pli grandaĝaj ol ili efektiva estas pro la liĥenoj, kiuj kreskas sur ili. Kiam vi iomete malsupreniras sub la rando de la kanjono, la arboj kreskas pli interproksimaj, kaj kun ili troviĝas kaliforniaj laŭroj. La kanjono ĝenerale malheliĝas, eĉ je sunlumaj tagoj, kvankam mi supozas, ke la suno povas eniri dum la malfrua posttagmezo kiam ĝi falas okcidente. Tamen estus nejuste nomi Krutan Kanjonon trista; kiel ĉia natura forto, ĝi superas tristecon, eĉ je la pli malhelaj tagoj.

La unua parto de la vojo kliniĝas malsupren laŭ nordenfronta herba deklivo punktita de mezaĝaj pseŭtocugoj, kies trunkoj ŝajnas pli grandaĝaj ol ili efektiva estas pro la liĥenoj, kiuj kreskas sur ili. Kiam vi iomete malsupreniras sub la rando de la kanjono, la arboj kreskas pli interproksimaj, kaj kun ili troviĝas kaliforniaj laŭroj. La kanjono ĝenerale malheliĝas, eĉ je sunlumaj tagoj, kvankam mi supozas, ke la suno povas eniri dum la malfrua posttagmezo kiam ĝi falas okcidente. Tamen estus nejuste nomi Krutan Kanjonon trista; kiel ĉia natura forto, ĝi superas tristecon, eĉ je la pli malhelaj tagoj.

The trail switchbacks down through the Douglas firs and laurels and eventually reaches the bottom of the canyon, where Webb Creek rages along westward on its short but enthusiastic course to the sea (in summer it will turn into a mere trickle, and this high up may even be dry). Here in the bottom the trees change form and become redwoods, with some really beautiful groves this high up -- further down they will spread out a bit and become more isolated from each other. Watch for two crossings of Webb Creek, only a few hundred feet apart, neither one of them with a bridge (you may get your feet wet); between them is a little spring, off to the right side of the trail, which in any season drains down onto the trail and turns it to mud, even when the rest of the trail is dust dry.

The trail switchbacks down through the Douglas firs and laurels and eventually reaches the bottom of the canyon, where Webb Creek rages along westward on its short but enthusiastic course to the sea (in summer it will turn into a mere trickle, and this high up may even be dry). Here in the bottom the trees change form and become redwoods, with some really beautiful groves this high up -- further down they will spread out a bit and become more isolated from each other. Watch for two crossings of Webb Creek, only a few hundred feet apart, neither one of them with a bridge (you may get your feet wet); between them is a little spring, off to the right side of the trail, which in any season drains down onto the trail and turns it to mud, even when the rest of the trail is dust dry.

Duan fojon transirinte la rivereton, vi dum iom da tempo restas sur aŭ super ĝia suda bordo, tra malhela arbaro, densa je sekvojoj, filikoj kaj aliaj plantaĵoj. Serĉu du-tri arbojn, kies korligno estas forbruligita -- bonaj lokoj por rifuĝi de ekpluvoj -- kaj ĝemelan arboduopon, inter kiuj vi devos paŝi; jen la fino de la arbareta regiono, kaj malsupre la kanjono fariĝas iom pli hela.

Duan fojon transirinte la rivereton, vi dum iom da tempo restas sur aŭ super ĝia suda bordo, tra malhela arbaro, densa je sekvojoj, filikoj kaj aliaj plantaĵoj. Serĉu du-tri arbojn, kies korligno estas forbruligita -- bonaj lokoj por rifuĝi de ekpluvoj -- kaj ĝemelan arboduopon, inter kiuj vi devos paŝi; jen la fino de la arbareta regiono, kaj malsupre la kanjono fariĝas iom pli hela.

One of the major problems along the Steep Ravine trail is fallen trees; after a stormy winter there will always be a few lying across the trail. One year the trail was actually closed for a month or so because of them (a ranger explained to me that they didn't want to clear them because there were "owls nesting in them"). This year I counted four or five along the route; two of them had fallen within a few feet of locations where the trail had been blocked in previous years by similarly fallen trees. The trunk of one was large enough that someone had felt the need to provide help in getting across; a large bolt was driven into the upward side, to hold onto while you scrambled from one side to another.

One of the major problems along the Steep Ravine trail is fallen trees; after a stormy winter there will always be a few lying across the trail. One year the trail was actually closed for a month or so because of them (a ranger explained to me that they didn't want to clear them because there were "owls nesting in them"). This year I counted four or five along the route; two of them had fallen within a few feet of locations where the trail had been blocked in previous years by similarly fallen trees. The trunk of one was large enough that someone had felt the need to provide help in getting across; a large bolt was driven into the upward side, to hold onto while you scrambled from one side to another.

Ĉefa ejo laŭ la vojo de Kruta Kanjono estas la Ŝtupetaro. Proks. duonvoje inter Pan Toll kaj la Vojkruciĝo Dipsea, vi malsupreniras tra mallarĝa fendo sur rokaj ŝtupoj kaj atingas la supron de la ŝtupetaro, kiu estas farita el ligno kaj havas proksimume 15 ŝtupetojn; ĝi kuŝas apud ĉefa falakvo de Rivereto Webb. Gardu vin, malsuprenirante laŭ ĝi; kiam ĝi malsekas (ofte!), la ligno povas esti glitiga, kaj mi ne certas pri la fortikeco de la ŝtupetoj -- en 1995, unu el ili rompiĝas, tamen oni poste refaris ĝin. Estas pli bone atendigi tiujn, kiuj suprenvenos, ol mem lasi vojon por ili; estas multe da spaco por staradu sub la ŝtupetaro, sed supre la sola spaco estas sur rukego super la falakva plonĝo -- starloko eble vigliga, tamen ne tre sekura, kaj certe ne sufiĉe spaca por pli ol unu persono.

Ĉefa ejo laŭ la vojo de Kruta Kanjono estas la Ŝtupetaro. Proks. duonvoje inter Pan Toll kaj la Vojkruciĝo Dipsea, vi malsupreniras tra mallarĝa fendo sur rokaj ŝtupoj kaj atingas la supron de la ŝtupetaro, kiu estas farita el ligno kaj havas proksimume 15 ŝtupetojn; ĝi kuŝas apud ĉefa falakvo de Rivereto Webb. Gardu vin, malsuprenirante laŭ ĝi; kiam ĝi malsekas (ofte!), la ligno povas esti glitiga, kaj mi ne certas pri la fortikeco de la ŝtupetoj -- en 1995, unu el ili rompiĝas, tamen oni poste refaris ĝin. Estas pli bone atendigi tiujn, kiuj suprenvenos, ol mem lasi vojon por ili; estas multe da spaco por staradu sub la ŝtupetaro, sed supre la sola spaco estas sur rukego super la falakva plonĝo -- starloko eble vigliga, tamen ne tre sekura, kaj certe ne sufiĉe spaca por pli ol unu persono.

Below the ladder I started seeing flowers. The most noticeable ones were trilliums. Most of the trilliums had not yet opened their buds, but a few disspirited looking flowers were already out; I suppose that by the second half of March the whole canyon will be in bloom. There were a few other flowers, but for a whole gamut of types I had to wait for the Dipsea Trail (see below).

Below the ladder I started seeing flowers. The most noticeable ones were trilliums. Most of the trilliums had not yet opened their buds, but a few disspirited looking flowers were already out; I suppose that by the second half of March the whole canyon will be in bloom. There were a few other flowers, but for a whole gamut of types I had to wait for the Dipsea Trail (see below).

Sekvu laŭ la kanjono dum ĝi plilarĝiĝas kaj poste remallarĝiĝas, kaj duonkilometron preter la ŝtupetaro vi malsupreniras al ligna ponto, kiu transiras al la norda flanko de la rivereto. Ĉi tie, transirinte, vi vidos maldekstre larĝan rokan spacon, kie la rivereto falas al kelkaj lagetoj, poste plonĝas trans la rando al granda lageto longe malsupere. Mi ne scias, ĉu tiu loko havas specialan nomon, sed mi mem nomas ĝin "Rokoj de Ripozo" ĉar mi kutime ekripozas tie por ĝui la rivereton kaj la ŝirmo de kelkaj grandaj superpendantaj arboj, se estus suno kontraŭ kiu ŝirmi vin... Ĉi tie ripozu kaj mem ĝuu la lokon.

Sekvu laŭ la kanjono dum ĝi plilarĝiĝas kaj poste remallarĝiĝas, kaj duonkilometron preter la ŝtupetaro vi malsupreniras al ligna ponto, kiu transiras al la norda flanko de la rivereto. Ĉi tie, transirinte, vi vidos maldekstre larĝan rokan spacon, kie la rivereto falas al kelkaj lagetoj, poste plonĝas trans la rando al granda lageto longe malsupere. Mi ne scias, ĉu tiu loko havas specialan nomon, sed mi mem nomas ĝin "Rokoj de Ripozo" ĉar mi kutime ekripozas tie por ĝui la rivereton kaj la ŝirmo de kelkaj grandaj superpendantaj arboj, se estus suno kontraŭ kiu ŝirmi vin... Ĉi tie ripozu kaj mem ĝuu la lokon.

The Dipsea and Steep Ravine trails now run together for some distance -- some very little distance, that is; not more than a hundred yards. Below the bridge, the stream widens into a pool in the summer, a pool from which water is sucked out to be lifted to a wooden tank far up in the woods to your right (you can see it from the Panoramic Highway). In the winter, the dam that creates the pool is opened and water is allowed to run free. I originally thought that the dam had broken in one particularly stormy winter, but after the spillway was seen to be open in quite a number of winters I came to the conclusion that the gate's disappearance was quite deliberate.

The Dipsea and Steep Ravine trails now run together for some distance -- some very little distance, that is; not more than a hundred yards. Below the bridge, the stream widens into a pool in the summer, a pool from which water is sucked out to be lifted to a wooden tank far up in the woods to your right (you can see it from the Panoramic Highway). In the winter, the dam that creates the pool is opened and water is allowed to run free. I originally thought that the dam had broken in one particularly stormy winter, but after the spillway was seen to be open in quite a number of winters I came to the conclusion that the gate's disappearance was quite deliberate.

Tiu mallonga vojparto estas la sola signifohava supreniro laŭ la vojo, kaj ĝi elkondukos vin el la eterna ombro al sunlumo -- aŭ nebulo, depende de la vetero, Post modera supreniro centmetra, vi atingos malgrandan fajrobrigadan vojon. Transiru ĝin, daŭrigu la supreniron al firsto, de kiu videblas la tuta panoramo de la marbordo Stinson Beach-Bolinas, kun la sabloetendaĵo de Stinson Beach, Laguno Bolinas, kaj la suda parto de Point Reyes -- unu el la plej belaj vidindaĵoj en norda Kalifornio. Kaj se la tago estas nebula, vi povas almenaŭ enmense bildigi ĝin al vi...

Tiu mallonga vojparto estas la sola signifohava supreniro laŭ la vojo, kaj ĝi elkondukos vin el la eterna ombro al sunlumo -- aŭ nebulo, depende de la vetero, Post modera supreniro centmetra, vi atingos malgrandan fajrobrigadan vojon. Transiru ĝin, daŭrigu la supreniron al firsto, de kiu videblas la tuta panoramo de la marbordo Stinson Beach-Bolinas, kun la sabloetendaĵo de Stinson Beach, Laguno Bolinas, kaj la suda parto de Point Reyes -- unu el la plej belaj vidindaĵoj en norda Kalifornio. Kaj se la tago estas nebula, vi povas almenaŭ enmense bildigi ĝin al vi...

From here you drop down to another fire road. Watch for fields of thistle in bloom late in the season; for those who know this plant only as a prickly annoyance, a first look at its beautiful round purple flowers (here they will be asccompanied by bumblebees en masse) will make you understand why the Scots chose this as their national emblem. If you want a side jaunt, turn left here and follow the road southwest until you come to the large tree you see off in that direction; then cast about downhill from the tree towards the highway, and you will find five old military spy holes, used to triangulate cannon fire from the batteries to the south in case of enemy invasion -- now abandoned to their fate, victims of a technological age with radar PPI and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

From here you drop down to another fire road. Watch for fields of thistle in bloom late in the season; for those who know this plant only as a prickly annoyance, a first look at its beautiful round purple flowers (here they will be asccompanied by bumblebees en masse) will make you understand why the Scots chose this as their national emblem. If you want a side jaunt, turn left here and follow the road southwest until you come to the large tree you see off in that direction; then cast about downhill from the tree towards the highway, and you will find five old military spy holes, used to triangulate cannon fire from the batteries to the south in case of enemy invasion -- now abandoned to their fate, victims of a technological age with radar PPI and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

De ĉi tie vi malsupreniras al ankoraŭ unu fajrobrigada vojo. Rigardu la kampoj da kardoj malfrusezone florantaj; por tiuj konantaj tiuj plantaĵon nur kiel pikeman ĝenaĵon, unua vido de la belaj rondaj purpuraj floroj (ĉi tie ilin amase akompanos burdoj) komprenigos vin, kial la skotoj elektis tiun floron kiel sian nacian floron. Se vi deziras flankan ekskurson, ĉi tie turnu vin maldekstren kaj sekvu la vojon sudokcidenten ĝis vi atingos la arbegon, kiun vi vidas tiudirekte; poste, serĉu sur la malsuprenira dekliva inter arbo kaj ŝoseo, kaj vi trovos kvin malnovajn militistajn gvatejojn, kiun oni uzis por trianguligi kanonpafadon de la sudaj baterioj okaze de malamika invado -- nun ili estas forlasitaj al sia sorto, viktimoj de teĥna epoko kun radara PPI kaj interkontinentaj misiloj.

De ĉi tie vi malsupreniras al ankoraŭ unu fajrobrigada vojo. Rigardu la kampoj da kardoj malfrusezone florantaj; por tiuj konantaj tiuj plantaĵon nur kiel pikeman ĝenaĵon, unua vido de la belaj rondaj purpuraj floroj (ĉi tie ilin amase akompanos burdoj) komprenigos vin, kial la skotoj elektis tiun floron kiel sian nacian floron. Se vi deziras flankan ekskurson, ĉi tie turnu vin maldekstren kaj sekvu la vojon sudokcidenten ĝis vi atingos la arbegon, kiun vi vidas tiudirekte; poste, serĉu sur la malsuprenira dekliva inter arbo kaj ŝoseo, kaj vi trovos kvin malnovajn militistajn gvatejojn, kiun oni uzis por trianguligi kanonpafadon de la sudaj baterioj okaze de malamika invado -- nun ili estas forlasitaj al sia sorto, viktimoj de teĥna epoko kun radara PPI kaj interkontinentaj misiloj.

If you have a car waiting for you in the park area, cross the Panoramic Highway and drop down to highway 1; then cross it (after getting some blackberries on the east side of the road -- in season, of course), and go north along the west side until you reach a road that turns left. Go down this road, keeping right at the immediate fork, for about a quarter of a mile; past the restaurant and snack shop you'll find a bridge across a stream and an opening in the park fence, through which lies the picnic area and parking lot. If you have time to kill, a visit to the beach is in order; aside from the beauties of ocean, sun and sand, you'll find plenty to interest you lying around in the sun picking up a tan -- again, in season.

If you have a car waiting for you in the park area, cross the Panoramic Highway and drop down to highway 1; then cross it (after getting some blackberries on the east side of the road -- in season, of course), and go north along the west side until you reach a road that turns left. Go down this road, keeping right at the immediate fork, for about a quarter of a mile; past the restaurant and snack shop you'll find a bridge across a stream and an opening in the park fence, through which lies the picnic area and parking lot. If you have time to kill, a visit to the beach is in order; aside from the beauties of ocean, sun and sand, you'll find plenty to interest you lying around in the sun picking up a tan -- again, in season.